It is practically a cliché at this point to begin an essay on Dada with an explanation of the name. But clichés are clichés for a reason and we return to them to show something new about the old. So let us revisit the fateful night when Tristian Tzara and Richard Huelsenbeck supposedly randomly stuck a knife into a French-German dictionary landing on the word Dada. Dada being nonsense, baby prattle, while also being the French word for hobby-horse.1 This essay will take us through an abbreviated history of the use of dolls and mannequins in the Dada movement, their inspirations, uses, and possible insights; so, it is fitting to begin by returning to the name which in some ways predict the use of toys, playfulness and perhaps the uncanny in the movement. This discussion will venture many fronts including the less playful references to mannequins. But for the sake of this introduction let us set our sight on dolls.

The Dada “Dolls” and Their Dolls

Dada is notable for the number of women who have cemented their legacy in its name. The most prominent three in Europe being Hannah Höch, Sophie Taeuber, and Emmy Hennings. While I don't wish to conflate all three of these women’s unique art practices in the name of gender it is of note that all three have created dolls or puppets in their lifetime and I would like to see the effect and interaction we can surmise by analyzing all three within the same piece of writing and within juxtaposing the use of the doll with the male Dadaist use of the mannequin. What similarities and differences can we find and how do these relate to childhood, gender, and art?

While Hennings, Taeuber, and Höch’s aesthetics, mediums, and locales all vary, the one common thread (despite the obvious case of gender) is their crafting of the poupée. Throughout this paper, I will use the term doll/puppet/marionette/and poupée interchangeably. There are of course important aesthetic and functional differences between all three for the sake of this paper we can locate all under the title of doll. However, it is important to differentiate between the Dada dolls stylistically and contextually and establish their importance within the dissemination of important Dada periodicals, which locate the women's doll-making solidly within the aesthetic foundations of Dada.

Let us first start with Hennings. The artist, performer, and poet Emmy Hennings was born in 1885 to a seafaring family in the coastal town of Flensburg, Germany. Describing herself as a seaman’s daughter she spent her life venturing from one town to the next finding work in the cabarets of Germany and encountering brief scandals and tragedy along the way.2 It is in Munich 1913 at the Cabaret Simplizissimus where she meets the piano player and soon-to-be revolutionary artist Hugo Ball. In 1915, due to the imminent threats of war, the performing pair relocated to Zurich and established the avant-garde performance space that is the Cabaret Voltaire. While Hennings is well noted and praised for her powerful and dynamic performances at the Cabaret Voltaire as well as for her poetry, which shows a melancholic and romantic view of modern city living, it is her poupées that are of interest for this paper.

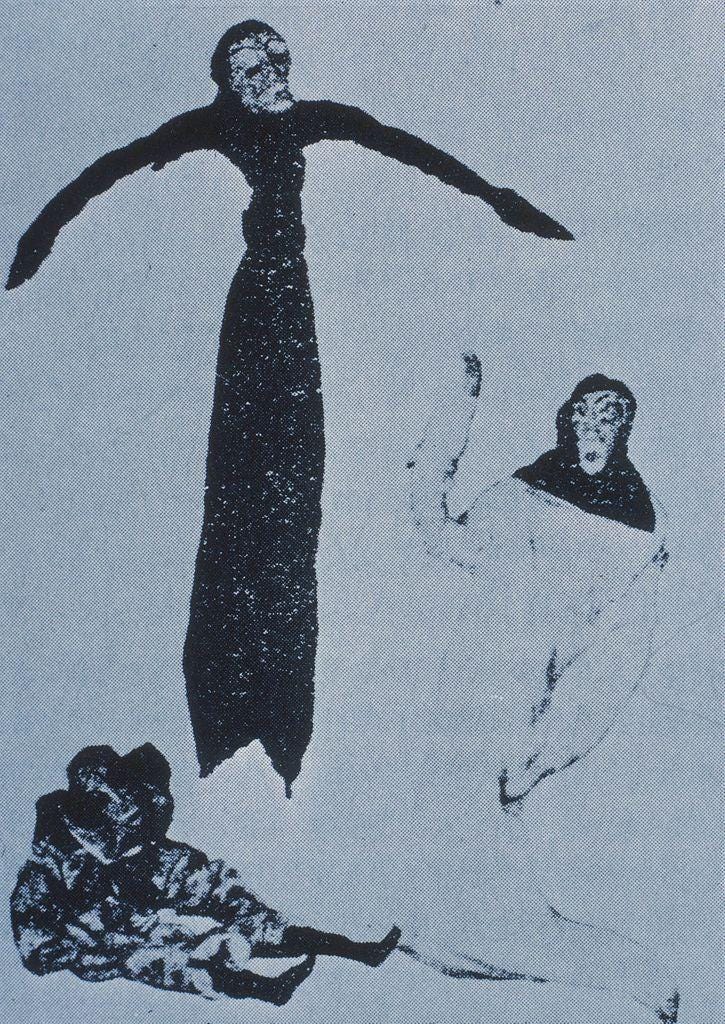

It is in the first and only edition of the magazine Cabaret Voltaire where Hennings is introduced prominently, with Ball, as the co-founder of the cabaret and where her poupées are given their spotlight. Three poupées are pictured with lanky, flaccid and indiscriminate bodies. Their faces are hollow, anonymous, and mask-like. The center puppet floats above the other two with its arms stretched out in a crucifix-style pose. The left-most figure slumps defeated in the corner while the right-most figure appears to be on its “knees,” hand, and head raised towards the center though it were praising and or defending itself against the more ominous central figure. This composition of the dolls also evokes imagery from spirit photography at the time. The shapeless forms of the dolls evoke the phantasmic appearances of supposed “ghosts” in these hoax photographs. One can see this more directly when comparing the photograph of Hennings dolls with the photograph of William Hope. Hope’s figures appear hooded, and their bodies float forebodingly over the other figures in the photos. As spirit photography has its roots in mourning perhaps this can lead us to a reading of Hennings’s dolls as performing some sort of grief.3

While the exact context of these dolls’ use is unknown, we can gather by their inclusion in the magazine, Cabaret Voltaire, alongside other canonical Dada works such as the drawings of Marcel Janco and the simultaneous poem L’Amiral Cherche un Maison à Louyer,4 that they were central to the decoration and performance of the Cabaret Voltaire. While we don’t know exactly how they were used, If they were played with like dolls, performed with like puppets, or stationary like statues we do know that they were important enough to be included in one of the first Dada publications and should be noted as a key aesthetic feature to the formation and execution of Dada. We can also gather from Hugo Ball’s diary that her dolls (not necessarily these ones) were in at least one instance activated politically as he notes the use of her puppets he calls the “czar” and “czarina” in a political puppet show, though seemingly the puppets were made by Hennings and performed by others.5 These political puppet shows predict the political puppet shows of Geroge Grosz in Berlin.6 Grosz’s use of the puppet’s larger-sized cousin the mannequin will be something we return to later in this discussion but let us continue with our dolls.

The other canonical poupée maker of the Dada movement is the prolific Swiss-born artist Sophie Taeuber. Taeuber and Hennings' art practices in some ways parallel each other, both being members of an artistic duo as well as both producing performances and puppets as part of their oeuvre.7 That being said Taeubuer’s art practice extends well beyond dance and puppets and goes on to include painting, collage, tapestry, and much more balancing on the line between “fine” and “applied arts.” In 1918 Taeuber was commissioned by the director of the Kunstgewerbeschule (the applied arts school in which she taught) to design the set and characters for a production of the Stag King, adapted from the 18th century Commedia dell’Arte fable by Carlo Gozzi for the opening of the Zurich Marionette Theater.8 The production Taeuber designed for heavily edited the original text and added characters such as a Freudian analyst to the cast of lovers, kings, and fools.

Taeuber’s puppets are segmented and cylindrical, almost cubist or pseudo-futurist in style while still keeping a colorful abstraction unique to Taeuber's work. Their colorful designs forgo the need for added costume and resemble the colorful and angular designs of the classic Commedia dell’Arte character of the Harlequin. Taeuber exacerbates the already inhuman elements of the marionette, giving her characters abstract faces and bodies. Some characters in fact are nearly completely inhuman such as the “guard” whose large silver pot-like body, four legs, six arms, and five heads evoke a monstrous machine more than they do a human. With the beast’s indiscriminate heads, machinelike body, and sword-bearing arms perhaps Taeuber is referring to the brutal dehumanization of the soldier at the time of the war. That being said, Taeuber does not totally sacrifice representation and leaves her characters with faces, arms, legs, and torsos in order for the audience to discern them as “humans” despite their inhuman appearance. Her designs feel reminiscent of the classical marionette figure enjoyed by children as both toy and theater.

Again les poupées grace the print world of Dada with one of Taeuber's marionettes being featured in the first and only issue of Der Zeltweg, a 1919 Dadaist publication edited by Otto Flake, Walter Serner, and Tristian Tzara.9 The choice marionette for publication was the Freudian Analyst, with its particularly phallic shape, perhaps it was chosen for its humor and timely satirical reference. For whatever reason, it was included, again solidifying the role of the poupée in Dada. It is also notable that in the same year Taeuber was commissioned to make these puppets she also crafts her first Dada head, Portrait of Hans Arp 1918. Perhaps inspired by her commission’s use of the miniature, the childish, and the toylike she creates these small sculptures, which are eerily reminiscent of a doll’s head. The Dada heads are distinctly sculptural and bust-like, tying them more to traditional art history than the history of the doll, so I will exclude them from analysis for this paper, but perhaps their inspirations have roots in the toy.

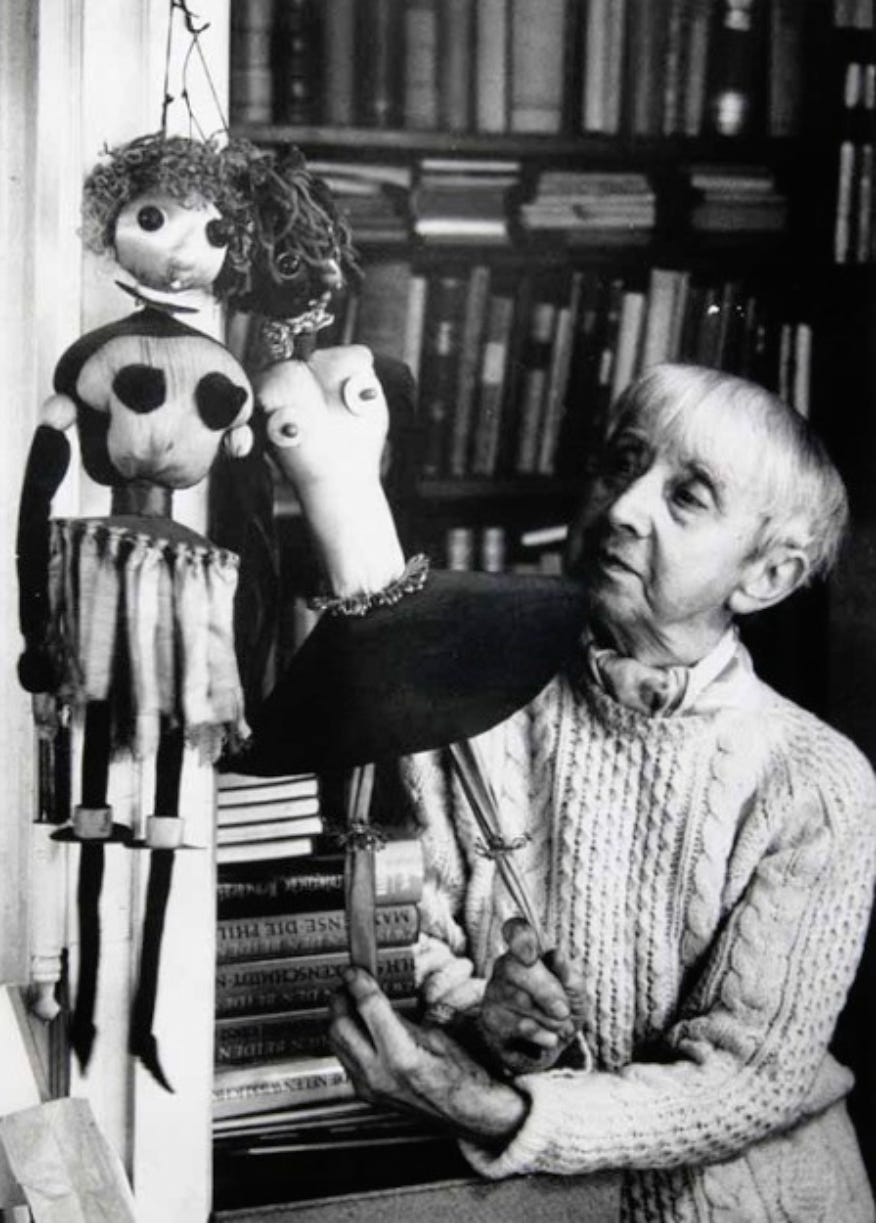

Our final Dada dollmaker is the Berlin-based proto-feminist Hannah Höch. Höch’s dolls are abstract and abject. They are rudimentary constructions with cloth, thread, yarn, and what appears to be beads or buttons. Resembling a child's handicraft. Their faces are simply constructed of two-tone button eyes, large noses, and simple mouths. Their hair is short and messy, perhaps resembling the new woman bob at the time sported and mocked by Höch. Their abstracted breasts are on display and their bodies resemble a characterized version of an ideal hourglass figure with large chests, cinched waists, and jutting-out hips.

Her dolls were included in the first international Dada fair in Berlin and featured in literary critic Max Reinhardt's periodical Schall And Rauch, the same name as Reinhardt's avant-garde cabaret. Unlike the other uses of Dada dolls in print Höch’s dolls are featured prominently on the cover and in a particularly stylized composition with added red graphic art highlighting the doll’s breasts, hips, nose, and hair, further extending the reading of these dolls as “naive” caricatures of the female form. It is from this publication that the painter Hans Hoffman is exposed to Höch's dolls and asks her to submit them to a show in Chicago where they were bought by Chicago painter Carl Sachs. Asserting again not only the importance these dolls had aesthetically in Dada but also the international reach they gained.

Höch’s photomontages, as well, seem to mimic, or function similarly to the paper doll. One plays with paper dolls by cutting them out of the given book, magazine, or printed material and arranging the outfits, accessories, and relations between the printed figures in ways that one finds amusing and pleasing aesthetically. This process replicates the process of photomontage, sans glue. While Höch’s montages are more abstract and aesthetically interesting than the children’s paper dolls, I think that there is weight in the fact of the material similarity. While it was beyond the scope of this paper to do archival research, I would like to posit future research that looks into the potential exposure Höch could have had to paper dolls with her work for the Ullstein publishing group and if this could have helped inspire the crafting the photomontage.

All three women, notably, have been photographed with their doll creations. Höch even sports a costume reminiscent of the doll she is holding with its dramatically flared skirt and stylized bustier and headpiece. Höch too looks her doll directly in the eye whereas in the photos of Hennings and Taeuber, they both stare outwardly with their gazes notably downturned. Both Hennings and Taeuber are depicted as distant from their dolls while Höch fully confronts the doll. Höch too has been photographed with her dolls well into the seventies when she was 85. This shows too that the dolls made and sold at the Dada fair are not the only dolls she crafted for these dolls stayed in her studio long after Dada died. In this photograph, she again has her signature loving gaze when looking at her dolls. Perhaps showing the special connection or relation Höch has with this aspect of her artistic creation. This special connection bridges the essay from the Dada history of the doll to the doll’s broader social history.

Social History of Les Poupées

The doll is an important figure in the girl child’s development and therefore becomes an important reference or symbol in the grown woman’s psyche. It is of note that all three of the previous Dada dolls discussed are consistently referred to by the creators as dolls or puppets, the French and German word for both being interchangeable, poupée and puppe respectively. I assert this now to solidly justify using the social history of the toy to analyze these works for these creations are obviously in reference to toys and are not miniature sculptures. These creations’ construction, as well, lend themselves to this reading. Both Henning’s and Höch’s dolls take on a sort of ragdoll body, reminiscent of children’s crafts and playthings, and Taeuber's marionettes, while stylized, distinctly borrow their forms from the children’s marionettes.

In his research on the role of the toy in German culture in the 19th and 20th centuries, David Hamlin notes the special and socially crafted relationship between girls and their dolls. While German boys were given a plethora of toys to choose from, girls were almost exclusively handed the doll. Not only were girls limited to the doll they were asked to love their dolls and care for them as if they were their children. Initiating the prepubescent girl already into the cult of motherhood and bourgeois domesticity. He notes that the girl child’s relation to the doll was seen and judged morally, as well, with a girl's refusal to play with a doll or care for it properly, being seen as a moral failure rather than a simple childhood preference.10

This oppressive play was noted by contemporary critics of the time. Charles Baudelaire in his 1834 essay “The Philosophy of Toys,” notes the potential power and creativity vested in childhood play. He notes that the toy is the child's first introduction to the visual arts and remarks on the creative power of children to turn almost anything into a doll, telling a story in abject awe of a child who uses a rat as a doll. But in his praising of the toy he makes sure to note that the girl children who played with dolls in ways that replicated their mothers’ domesticity (childrearing, social calls, etc) were to be pitied for they are excluded from this abstract and creative play, he saw as formative in the aesthetic lives of children.11

In The Second Sex Simone de Beauvoir notes the role and importance the doll has in the girl child’s life and how this carries on into adulthood. Beauvoir notes the same oppressive power that Hamlin and Baudelaire observed in the doll but extends her analysis citing not only its forced domesticity upon the girl child but also its power to indoctrinate the girl child in the role of objecthood. The girl child is asked not only to care for the doll but to also see herself in the doll, to identify with the doll. She notes this continued identification with the doll into adulthood and references the common usage of the word “doll” to refer to adult women, in a somewhat sexual and derogatory way. Beauvoir notes that despite the conditioning these dolls were supposed to enforce upon girl children, the child could still find autonomy within their doll play. Being thrust into the role of the doll's mother granted the girl authority over the doll and one could punish and scold the doll, as one was punished or scolded by parents, putting the little girl in the subject position of authority figure. For de Beauvoir the doll is both a vehicle of women's objectification as well as her means for liberation into subjecthood.12

Using Beauvoir's subversion of the power of dolls as well as Baudelaire's noted potential for the creative play and aesthetic education found in dolls we can start to see the doll as a charged site of formation for the creative subject. While Baudelaire chides the female child's use of dolls as uncreative mimesis of bourgeois femininity, he praises the general childlike creative power to make a doll out of anything from rubbish to a live rat. The Dada dolls described earlier function more like the rubbish doll Baudelaire describes. Not one of the three women's dolls could be described as beautiful, in the same way we describe a woman or a classically produced doll as beautiful. Taeuber's are the most aesthetically pleasing but they are not representative of the beauty of the female form and Hennings dolls are bare and ominous while Höch's are messy and abrasive. In this way, the Dada dolls escape Beauvoir’s accusations of objectification and personify the power of the formation of the subject for these women assert their positions as creative subjects through the crafting and dissemination of these dolls and use these dolls to firmly cement their positions within the movement of Dada.

If the power of the doll is two-fold, both site of objectification and subjectification, we can see the power of the latter on display in the abstract and creatively independent dolls of the Dada women. The former is displayed and subverted more thoroughly in Höch’s photomontages of the late 20s and 30s such as Shattered (1925) and Love (1926) where she takes advertisement images of the bisque doll,13 the doll that is most associated with German bourgeois childhood femininity and splices it into cunningly subversive compositions which critique the aesthetics of femininity as well as heterosexual relationships. These dolls, though, function much differently than her crafted rag dolls. Here Höch takes the readymade image of the doll, loaded with the objectifying power Beauvoir comments on, and shatters and fractures that power in order to create a more direct comment on gender. Her ragdolls, along with Hennings and Taeuber's puppets, have more to say about the childish, “naive” or for lack of a better word “primitive” aesthetics of Dada which goes back to where we started this essay with Dada’s namesake referring not only to childish prattle but also to a child’s toy, the hobby horse. Without falling into the pit trap of the femme-enfant of the Surrealists, the Dada women’s dolls seem to truly embrace the anti-art sentiments of the Dadaists and channel aspects of nonsense and play that were essential to the movement.14

The Dada MAN-nequin

Since we have completed our survey of the use of dolls in the femme oeuvre of Dada we may now be wondering where the doll is in the work of male Dadas. As a modern scholar one does not posit one medium as inherently more feminine over another, collage, performance, and tapestry have all been made by both men and women within Dada so are dolls any different? While there may not be any male Dada dolls, there are Dada mannequins and with a proper examination, we may see how they function in similar ways to the Dada doll but with distinctly different reference points.

The two Dada mannequins I wish to discuss are Prussian Archangel and The Petite Philistine Heartfield Gone Wild (Electro-Mechanical Tatlin sculpture) both created in 1920 for the First International Dada Fair, the former being constructed by John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter, and the latter by Heartfield And George Grosz. Both figures appear in a surviving photograph we have of the fair. Prussian Archangel hangs above the crowd with the military costume of a Prussian army officer and the head of a pig, its torso is straight and stiff and its legs twisted in awkward angles. Upon the figure hangs two signs one quoting protestant reformer Martin Luther and the other stating that in order to understand the piece one must “exercise each day for twelve hours on the Tempelhof field armed for battle and carrying a fully-loaded knapsack.”

The second Dada mannequin Heartfield Gone Wild uses a child-sized tailor dummy while replacing key features with mechanical counterparts, a lightbulb for a head, a lampstand for a leg, and a revolver for an arm are just some of the appendage replacements made in this assemblage. Again the themes of soldierhood appear, with the figure bearing a pseudo-war medal made out of dining utensils and the use of a weapon as replacement for an arm. Brigid Doherty extends this reading by drawing a connection between the sporadic lines drawn on the base to the repetitious military drills that would be performed in training camps.15

In Matthew Biro’s text on the Dada cyborg, he remarks that the Prussian Archangel is a citational work of art, with the obvious citations being to the military uniform and the role of Protestantism in German culture.16 He believes these citations are exemplary of the critique of the total mobilization of the front. The belief that all aspects of German culture were aimed toward crafting a better and more effective military. This includes what Biro cites which is the use of Protestantism to uplift the soldier to aspects of femininity, childhood, and marriage. I wish to extend these citations to that of the mannequin, for these assemblages are obviously not sculptures. They aren't carved, modeled, or cast they are put together. And if Heartfield, Grosz, and Schlitner are citing the mannequin what might that citation mean?

The Mannequin

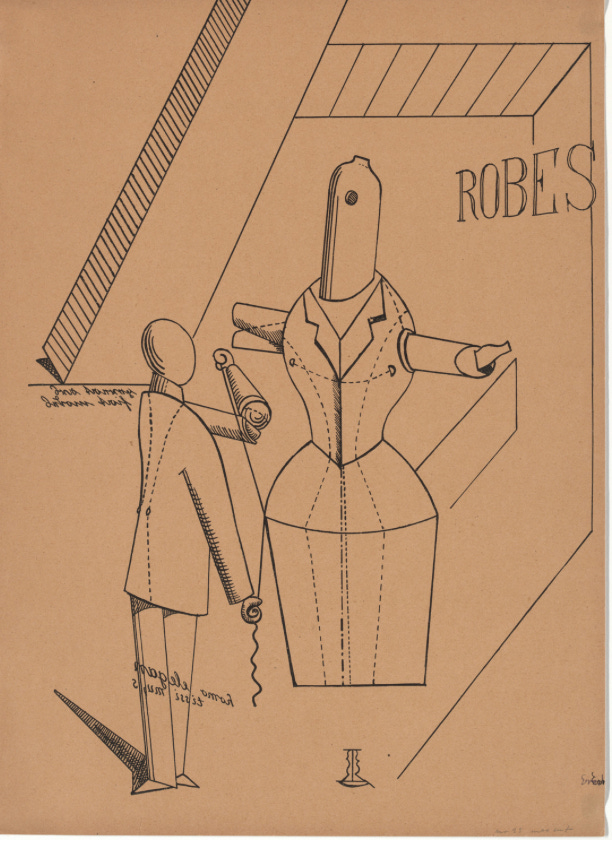

The mannequin has its beginnings in the studios of Renaissance artists and was used well into the 19th century for studies of drapery and anatomy as well as body replacements for more difficult-to-hold poses.17 The mannequin is inherently tied to the canon of art history and is used frequently both as tool and subject of the artist both before and after Dada. The highly influential 20th-century painter Giorgio de Chirico uses an anonymous mannequin to populate his proto-surrealist compositions. Max Ernst picks up the de Chirico use of the mannequin in his series of lithographs, Fiat Mode, created during his Dada years in 1920. The mannequin becomes a mainstay in the surrealist oeuvre as well, with sixteen mannequins crafted by the likes of former Dadaists such as Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, and Max Ernst lining the hallways of the 1938 Exhibition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris. Smaller poseable figure drawing mannequins still line the aisles of art supply stores to this day.

The mannequin also has intrinsic links to commerce. The mannequin begins behind closed doors in the ateliers of artists and fashion designers. But as fashion becomes more industrialized and clothing sizes become standardized rather than made to the wearer the mannequin exits the atelier and enters the market.18 Photographs by Eugene Atget show the prevalence of the mannequin in the 20th-century shop windows of Paris. Marcel Duchamp writes a note to himself in 1913, about being “interrogated by shop windows” and of “the demands of the shop windows,”19 and while he does not particularly specify the mannequin as the demander or the interrogator, we can assume these humanoid creations played part in Duchamp’s choice words of personification. In the previously mentioned Fiat Modes by Max Ernst, the inscription is given on the first plate “fiat modes pereat ars” meaning “Let there be fashion. Down with art,” showing the awareness these artists had of the threat that the “fashionable” or the commodity faced on art, with mannequin being one of the most recognizable reference points for the market.

Not only was the mannequin used for commerce, but it also had its role in the military. Used both in military testing as well as decoys. An Illustration from a June 1916 edition of Le Petit Journal, a conservative French periodical, shows rudimentary stuffed mannequins dressed in German military uniforms, placed strategically in the trenches in order to draw fire and confuse their Russian combatants. Photographs as well show mannequins or dummies being used in place of soldiers, in decoy war tactics. One photograph shows French soldiers posing with their artificial counterparts. These illustrations and photographs highlight the fraught relationship that soldiers would have had with these mannequins. They are saviors, meant to be sacrificed in place of the real men in order to exhaust enemy fire. But they are also ominous forecasters, highlighting the soldiers’ real role in the military, to be faceless, nameless, anonymous, and expendable.

Another prominent reading of the mannequin is that of the uncanny. The mannequin as a port between life and death, distinctly both human and object. Of course, the question of the Uncanny is relevant when discussing humanoids and automatons but I believe Freud’s notion of the Uncanny better fits the surrealist use of the mannequin than the Dada use. With notions of castration and dreams, the analysis Freud does of the role of the mannequin fits the sexualized femme mannequins of the surrealists rather than the more political constructions of the Dadaists. The Dada mannequins, to borrow Birro’s term, are more “citational.”

Going back to Biro’s text he finds a sort of subversive humor in Prussian Archangel that fights against the authority of the German state.20 The replacement of the head with the visage of a pig undermines the supposed authority of the regalia of the Prussian army officer. Adding my own analysis They string him up like a marionette and bend his arms and legs to their will. One could say they played with the mannequin, they dressed him up and posed him as if he were a large puppet or doll. This play subverts the authority of the Prussian officer and perhaps fights against the objectification of the male soldier into a mannequin or dummy used as sacrifice in the name of war. In Heartfield Gone Wild the play is more doll-like than marionette. While others have theorized that the smaller child-sized dummy represents the regressive mindset of the returned soldier.21 I suggest that the smaller appearance of the mannequin allowed Grosz and Heartfield to “play” with their assemblage; to dress the mannequin up as if it were their doll. This playful subversion works in a similar fashion to the Dada dolls.

Conclusions

Birro in his analysis of our Dada mannequins suggests a reading of the figures as subversive of Ernst Jünger’s theory of “total mobilization,”22 and perhaps the concept of “total mobilization” allows us to tie a bow on this connection between the mannequin and the doll. While the mannequin’s connections to the military and combat were more clear, with the mannequin being used directly in trench warfare, the doll has a more subtle yet just as pertinent connection to the war. As Ernst Jünger writes in his essay on total mobilization

“In the final phase, which was already hinted at toward the end of the last war, there is no longer any movement whatsoever-be it that of the homeworker at her sewing machine without at least indirect use for the battlefield, In this unlimited marshaling of potential energies, which transforms the warring industrial countries into volcanic forges, we perhaps find the most striking sign of the dawn of the age of labor. It makes the World War a historical event superior in significance to the French Revolution.”23

Jünger’s point emphasizes the importance of the homefront, as he highlights the uniqueness of World War One as instigating an opaque and encompassing energy of war. He makes a point that this “total mobilization” crosses the gender lines and enters the world of the domestic, with the “homeworker at her sewing machine.” While Jünger prioritizes an industrial and labor-centered analysis, we can extend this to a social reading as well. We explored the doll earlier as a rich symbol of bourgeois femininity loaded with, as Hamlin noted, the moral values of the German bourgeois class. The doll then could possibly be read as a tool to breed docile and subservient future mothers, who will birth, raise, and send off to war the future good German soldiers. Just as the mannequin in the shop window and the dummy on the battlefield train the German man to be anonymous and expendable soldiers and consumers. Both doll and mannequin, richly filled with their respective cultural weight, are playfully subverted by the Dada artist to critique the culture of war, consumerism, and femininity in early 20th century Europe; and while not as prominent as the photomontage or the readymade these humanoid constructions deserve their place in the canon of Dada.

Richard Huelsenbeck, En Avant Dada: A History of Dadaism, trans. Ralph Manheim (Paul Steegemann Verlag,1920), 24.

Thomas F. Rugh, “Emmy Hennings and the Emergence of Zurich Dada,” Woman's Art Journal 2, no. 1 (1981): 1.

Jen Cadwallader, “Spirit Photography Victorian Culture of Mourning” Modern Language Studies 37, no. 2. (2008): 8-31.

Cabaret Voltaire, ed. Hugo Ball, (Zurich, 1916), Dada Digital Collection, Iowa Digital Library, Iowa University Libraries.

Hugo Ball, Flight Out of Time, trans. Ann Raimes, ed. John Elderfield (University of California Press, 1996), 102.

Thomas F. Rugh, “Emmy Hennings and the Emergence of Zurich Dada,” Woman's Art Journal 2, no. 1 (1981): 3.

Renée Riese Hubert, “Zurich Dada and its Artist Couples” in Women in Dada: Essays on Genders, Sex, and Identity ed. Naomi Sawelson-Gorse (MIT Press, 1999), 527.

“Biography: Sophie Henriette Gertrud Taeuber-Arp,” Gabrielle Mahn accessed, Dec 23, 2024, https://sophietaeuberarp.org/english/biografie/.

Der Zeltweg, ed. Otto Flake, Tristan Tzara, and Walter Serner, (Zurich, 1919), Dada Digital Collection, Iowa Digital Library, Iowa University Libraries.

David Hamlin, “A World Made for Exploration: Germans and their Toys 1890-1914,” in The World of Children: Foreign Cultures in Nineteenth Century Education and Entertainment, ed. Simone Lassig and Andrea Weiss (Berghahn Books, 2019), 263.

Charles Baudelaire, “The Philosophy of Toys,” in On Dolls, ed. Kenneth Gross (Notting Hill Editions, 2023), 42-45.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (Vintage Books, 2011), 293-297.

Die Woche 32, no. 49 (December 1930): 1459.

Margaret R. Higonnet, “Modernism and Childhood: Violence and Renovation,” The Comparatist,Vol. 33 (2009): 89.

Brigid Doherty, ““See: "We Are All Neurasthenics"!" or, the Trauma of Dada Montage,” Critical Inquiry 24, No. 1 (1997): 121.

Matthew Birro, The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin (University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 173-175.

Katie Scott and Hannah Williams, Artists Things: Rediscovering Lost Property From Eighteenth Century France (Getty Publications, 2024), 200.

Sara K. Schneider, “Body Design, Variable Realisms: The Case of Female Fashion Mannequins,” Design Issues 13, no. 3 (1997): 6.

Marcel Duchamp, Ecrits: Duchamp du Signe, ed. Michelle Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, (Flammarion, 1975), 106-107.

Matthew Birro, The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin (University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 175.

Brigid Doherty, ““See: "We Are All Neurasthenics"!" or, the Trauma of Dada Montage,” Critical Inquiry 24, No. 1 (1997): 107.

Matthew Birro, The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin (University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 177-179.

Ernst Jünger, “Total Mobilisation”, trans. Joel Golb & Richard Wolin in Richard Wolin (ed.), The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader ( MIT Press, 1998), 126.